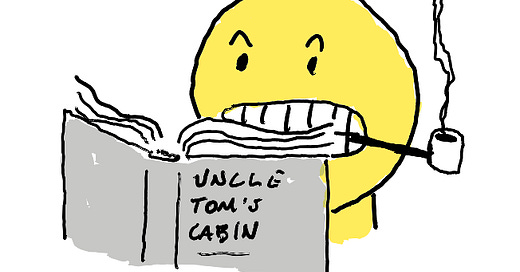

The answer is that many academic (and other) readers still object to Uncle Tom’s Cabin on political and moral, rather than aesthetic, grounds. In fact, readers have been objecting to the novel on these grounds since its 1852 publication. I thought that Substack readers might be interested in a relatively breezy recap of the reputation of Uncle Tom’s Cabin throughout the nineteenth and twentieth century.

Let’s turn history’s pages, shall we?

The Mid-Nineteenth Century

When it was first released, Stowe’s novel was hailed as a masterpiece by many readers, especially Northern and antislavery readers. Of course, proslavery readers didn’t like the book because they disagreed with its antislavery message and usually argued that it exaggerated the harms of slavery. (They had many nasty things to say about Stowe, a woman who dared to speak on political issues, even through the alembic of a novel.) But many proslavery or non-anti-slavery readers were forced to admit the novel’s power. “Its fidelity, its fairness, its morality we may venture to discuss,” wrote one Southerner in the New York Times, “but it would be idle to deny that it is a powerful appeal to humanity; that it moves the soul in its very depths; and that it awakens the intensest interest in the fortunes of the humble hero of the story.”

But not every anti-slavery reader loved the novel. Martin R. Delany, the famed abolitionist, criticized the novel in the pages of Frederick Douglass’ Paper. Delany had a number of complaints about the novel. First, Stowe made a great deal of money speaking on behalf of black people, who were, as he pointed out, perfectly capable of speaking for themselves. “I beg leave to say,” he wrote in one letter, “that she knows nothing about us…neither does any other white person—and, consequently, can contrive no successful scheme for our elevation; it must be done by ourselves.” Stowe took the story of Uncle Tom from a real, formerly enslaved man, Josiah Henson, who, Delany argued, she should give some of her profits to—and she took other fugitive slave narratives, too, blending them into a storyline that would be palatable for whites and profitable for Stowe. Next, Delany argued, Stowe was a Colonizationist! Colonization was a racist scheme to essentially deport all free black people from the United States. It was purportedly an anti-slavery effort but was supported by slaveholders and was considered by many abolitionists and free black people to be a racist and proslavery scheme—so Stowe’s book was politically flawed, for Delany. Finally, Delany argued that Stowe was, essentially, a racist, who preferred black people to remain subordinate and obedient.

In the pages of his paper, Frederick Douglass pushed back, arguing in essence that black people and abolitionists needed every friend they could get, and that an enormously influential novel arguing against slavery could be nothing more than a great help to the cause. And there is good reason to think that Delany was not a trustworthy reader of the book, given that he admitted that he had never actually read it!

Still, Delany’s chief objections—a white author taking the stories of slaves and turning it into profitable and mass-market-ready product; her flirtations with colonizationism, and her racism—are, I think, among the chief objections that many scholarly readers take to the book today.

The Late Nineteenth Century

When Uncle Tom’s Cabin was published, it almost immediately was turned into a stage show. And, as the decades passed, some versions of this stage show became more and more removed from the antislavery message of Stowe’s original novel. They became spectacular to the point of silliness On the idea that more is always better, stage shows advertised that their production had not one but two (or three or four) Uncle Toms—or had live dogs—or had great special effects. Playwrights adapting Stowe’s book introduced new characters, usually for comic effect, and began portraying Tom not as a robust, manly hero but as an ineffectual old man. The theatrical shows became, in essence, embarrassing pop culture, although they remained popular for decades.

But the novel itself, although it continued to sell well, also started to become something of an embarrassment. A new literary-critical consensus began taking shape, beginning in the 1850s with the advent of new highbrow magazines like The Atlantic but especially after the Civil War: didactic or propagandistic literature was no longer considered good literature or even, in some cases, literature at all. Key critical figures of this age, like W.D. Howells and Henry James, began explicitly arguing that novels should not make direct moral appeals to their readers, and that didacticism was necessarily a flaw. By the time Edward Bellamy’s blockbuster utopian novel Looking Backward came out in 1888, many critics even argued that it should not be considered a novel or even fiction—merely a work of sociology or a socialist tract. Direct moral appeals of the kind used by Stowe now made works of art illegitimate, or at least located them outside of the genre of imaginative literature. And so Uncle Tom’s Cabin lived on as a silly stage show, a piece of popular culture, a book for children, a nostalgic book fondly remembered—but not as an urgent masterwork.

The Early Twentieth Century

In the 1910s, as the scholar Adena Spingarn (Uncle Tom: from Martyr to Traitor) reports, the phrase “Uncle Tom” started to become a derogatory slur denoting a self-serving race traitor. Spingarn suggests that this was not in response to theatrical versions of the show (which she argues were not quite as bad as their current-day reputation would suggest) but was because the character Uncle Tom had grown to represent slavery itself. In an environment where “the days of Uncle Tom” just meant “slavery,” black American activists and writers wanted to distance themselves from Uncle Tom as much as possible. These activists wanted a sense of progress—of moving past the days of Uncle Tom and into a progressive age of equality. And so “Uncle Tom” became written off, both as a character and as a novel.

At the same time that these political changes were happening, though, the critical consensus that didactic, political novels were necessarily flawed continued to harden amid the advent of literary modernism, a movement that tended to emphasize the autonomy of art—“art for art’s sake”—and which often expressed profound skepticism of the moral universalism that animated Stowe’s art.

This is not to say that didactic literature disappeared—just that it was not at the forefront of the most exciting aesthetic and critical developments of the early twentieth century. (And there were notable holdouts who continued to defend Uncle Tom’s Cabin, like W.E.B. Du Bois.) There was socialist realism and the novels of commitment and powerful protest novels like The Grapes of Wrath and Native Son. But the latter of these novels was singled out as a particularly heinous protest novel in the most famous essay ever written about Uncle Tom’s Cabin: “Everybody’s Protest Novel” by James Baldwin.

Baldwin’s essay is well worth reading—ultimately I disagree with it, but it is short, vivid and well-written. In it, he inveighs against what he sees as the novel’s refusal to grant any of its characters their full humanity. Everything is too morally neat, too inhuman; the protest novels are “a mirror of our confusion, dishonesty, panic, trapped and immobilized in the sunlit prison of the American dream. They are fantasies, connecting nowhere with reality, sentimental.” The task of good art, argues Baldwin, is to show the “beauty, dread, power” of the human being, not to argue for it desperately in a way that ultimately betrayed the novelist’s lack of faith in their belief. Baldwin was suspicious of sentimentality—his sense that it was deeply insincere and inhuman—and political commitment in the novel. He wanted “ambiguity” and “paradox”—and in making this complaint, his essay was one expression of the sensibility that had been slowly dominating American high-culture literary criticism since the end of the Civil War.1

The Late Twentieth Century

For me, the two most important late 20th-century readings of Uncle Tom’s Cabin are by Ann Douglas and Jane Tompkins. They both focused on the novel’s political properties, not necessarily its aesthetic qualities.

Douglas thought that sentimentalism was a political trap. “Sentimentalism,” Douglas wrote, “provides a way to protest a power to which one has already in part capitulated. It is a form of dragging one’s heels…Little Eva’s beautiful death, which Stowe presents as part of a protest against slavery, in no way hinders the working of that system.” Eva’s death, the novel’s most famous scene, is here read a consumeristic indulgence for middle-class women who preferred consumption to action, influence to power, passivity to activity. And the entire project of sentimentalism was accordingly suspect, precisely because it was not sufficiently resistant to power. Stowe’s radical novel was not radical enough.

Tompkins, in contrast, praised the novel—and praised formulaic, stereotypical, and sentimental literature in general—not on the grounds of aesthetic enjoyment per se but because it did great “cultural work,” expressing a powerful radical critique of American culture through conventional literary devices. Speaking of sentimental novels, including Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Tompkins writes: “Their familiarity and typicality, rather than making them bankrupt or stale, are the basis of their effectiveness as integers in a social equation.” If we study books based on how influential they are, as opposed to how “good” they are according to our aesthetic sensibilities, we’ll be able to construct a history of literature that focuses on what literature does within society.

After all, as Tompkins points out in the book’s final chapter (which is, for my money, a model of great academic-critical writing—clear, lucid, direct, provoking), our aesthetic standards change all the time! The standards of judgment that critics use to decide which books are good and which are bad shifted dramatically over the course of the twentieth century. They’re not reliable, nor are they obviously based on fact—they’re under negotiation constantly. So why not, Tompkins asks, choose to value works like Uncle Tom’s Cabin—not for “imaginative vitality” and their ability to speak to the “soul of man”—but because they “[do] a certain kind of cultural work within a specific historical situation”?

I think it’s a great argument, and I don’t dispute it in the specific context of historicist academic research on literature. But it also has some potential shortfalls. For example: If we choose to value literature based on the cultural work it performs, then the question of what literature is good transforms into the broader moral/political question of what cultural work is good. It makes no sense, for example, to value a bestselling sentimental novel that does horrible cultural work (e.g. Thomas Dixon’s pro-KKK Reconstruction trilogy, the first book of which sold 200,000 copies in 1902 alone)—it only really makes sense to value beneficial cultural work. So then the ultimate question for literary critics is not distinctive to literature but is the far more vague and difficult: what does it mean to “improve” culture? What is “the good,” morally and politically speaking? And this presents all sorts of problems, among them that literature professors are trained to be experts on imaginative literature and its distinctive properties, not moral gurus or fonts of political wisdom.

At the same time, if literature truly can be a powerful force for political change in the world—as I believe it has been and can still be—we need to reckon with its political/moral dimensions, and that necessarily entails making arguments about “the good” more broadly speaking. Novels and poetry are morally significant documents. We can’t hide away from that part of literature. At the same time, thinking about novels only as rhetoric and subject only to political and moral evaluation seems reductive.

But let’s bring this back to Uncle Tom’s Cabin. The long and short of it is that Tompkins’ argument was successful! Even those critics who disagree with Tompkins’ assessment of UTC agree on her basic terms: the novel is criticized, when it is criticized, for doing bad cultural work. I want to close out with a brief summary of some of these moral/political critiques. To be clear: I don’t necessarily hold these views! I’m summarizing the views of others to provide more context for interested readers.

Sentimentalism is corrupt.

Echoing the line of thought going through Baldwin and Douglas, some readers see the novel’s sentimental tropes and attempts to evoke sympathy from readers as either inherently conservative or at least anti-radical. Sentimentalism was, these critics argue, a way for bourgeois, middle-class readers to feel virtuous: “I’m such a good person because I cried at this novel in sympathy with the oppressed!” Then, those readers proceed to do nothing politically, feeling absolved of their responsibility to take action because they have already, as Stowe puts it at the end of UTC, “[seen] to it that that they feel right.”

Uncle Tom’s Cabin is racist.

Critics have been quick to note the novel’s use of “romantic racialism”—the idea that certain races have inborn traits. Stowe specifically believed that black people were by nature childlike, emotional, “simple,” and docile. (She refers, at one point, for example, to “their gentleness, their lowly docility of heart, their aptitude to repose on a superior mind and rest on a higher power, their childlike simplicity of affection, and facility of forgiveness.” This sort of thing is not particularly scarce in the novel.) Whites, on the other hand, were natural conquerors, intellectual, imperious. (Augustine St. Clare argues that slaves will only rebel because they have “Saxon blood,” for example, and George Harris, the ingenious and rebellious black man, is so light-skinned that he can pass as a Spanish gentleman.) She thought that these natural differences made black people superior Christians to whites, but it is not difficult to understand why not all readers might understand this sort of racial thinking as complimentary. Richard Yarborough’s “Strategies of Black Characterization in Uncle Tom’s Cabin and the Early Afro-American Novel” is the place to start reading about this. Elizabeth Ammons has also critiqued the novel along similar lines.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin is colonizationist.

At the end of the novel, Stowe sends the fiery rebel George Harris to Liberia, marking her, for readers from Delany onward as a colonizationist. Many scholars refer to Stowe’s “colonizationist” views in passing. Stowe later repudiated colonization, telling an abolitionist convention that, if she had to do everything over again, she “would not send George Harris to Liberia.” But, paired with her views on race, the novel can look pretty politically regressive—at least as politically regressive as it is possible to be while still arguing against slavery. I think these critiques need to be contextualized—but to find out why, you’ll have to read a peer-reviewed article that I hope will be accepted soon!

Uncle Tom’s Cabin’s gender politics are retrograde.

This is one critique that wasn’t levied by Delany, but it still an important angle of criticism on the novel. Basically, Harriet Beecher Stowe idolized socially-conventional social roles, especially that of mothers. She participated in what historians call the “Cult of True Womanhood,” an ideology that supposed that women were naturally more moral, pious, domestic, and submissive than men. This was despite the fact that Stowe herself chafed against this standard and in some cases failed to live up to it, as her biographer Joan Hedrick shows! But the moral crux of Stowe’s novel is this: a mother’s love for her children is the most powerful emotive force in the world, and a mother’s love is felt with equal depth and power by black and white people. But if you’re highly skeptical of the forms that motherhood took in the nineteenth century, such moralizing might come off as suspect to you, in one form or another.

End

OK, that was a very long post. If you’ve stuck through to the end, hooray for you—you have a skeletal but not terrible understanding of the academic-critical reception of Uncle Tom’s Cabin! But in conclusion, I will note that a more positive attitude toward Stowe’s novel has taken hold in the academy in the past few decades. The best book for general readers on this is David Reynolds’ Mightier than the Sword, which argues at length that UTC is not only good literature but is actually morally and politically defensible.

The novel is, by now, canonical—it’s widely assigned, and anybody who seriously studies nineteenth-century American literature must have read the book. But the fact that it is widely studied does not necessarily mean that it is widely respected. I would characterize the current academic reputation of the book as divided: some see it as a masterpiece of great moral power, and some see Stowe as, in essence, a well-intentioned middle-class do-gooder who was morally insightful but also fundamentally blinkered by some of her views on topics like race and gender, and by the sentimental conventions that she uses to such extraordinary effect in Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

It should be noted, although in the interest of brevity I won’t go too into it, but many of these critiques, and later defenses, of sentimentalism were concerned with gender: sentimentalism was seen as a woman’s genre, as it was primarily written and read by women, and the establishment of this paradoxical, ambiguous literary standard is often a reaction against the popularity of women’s literary art.

This is incredible! What a great rundown of this response. I vaguely knew it, but not really.

What I don't like about Tompkin's argument, as I understand it, is that this downplays the artistry of the book. It's not just a sentimental novel about race, and it doesn't just work by evoking strong emotions. There is an essential fairness to the book that I think many people can recognize--a fairness that is missing from most didactic literature. Even contemporary critics acknowledged that if slavery entailed the abuses she pointed out, then it would be wrong. They simply disagreed that, for instance, families were routinely broken up under slavery. But we know now that her portrait was factually accurate. She did give a complete picture of slavery as it was actually practiced, and of slavery's practitioners as they actually lived and thought, in all their variety. That's what makes it great literature, not just that her aims were good.

Love this post, especially because "I didn't read it but I want to comment on it" turns out to have started with mass literacy.