What It’s Like to Get a PhD in Literature

I have been working on a PhD in English for the past five years or so. My life is probably not particularly interesting to most people, but it occurs to me that some might want to read a frank account of what it’s like to go through a literature PhD program, especially if they are considering getting a PhD in literature themselves or are interested in the current state of humanities academia. So here are a set of small vignettes explaining, from my perspective, what it’s like to get a PhD in literature.

Getting into a Program

In most cases, it is easier to get into a PhD program than schools would like to make you think. The currency of humanities academia is prestige, and the only reliable indicator of prestige is exclusivity, so institutions try to seem as exclusive as possible. Don’t let this scare you too much. Suppose, for example, that a school receives 150 applications and admits ten students. You might think that only the best 7% of students will receive an offer of admission. Not so! The best twenty or so applicants will likely receive offers from multiple schools, and many of them will choose not to enroll. So the “initial yield” (the number of students, out of those who are initially admitted, who enroll) is often rather low—say 25%. If the yield is 25%, there are still five spots left, which the program will offer to ten more applicants. The program may have to offer admission to twenty-five or thirty students before they fill all of the available spots. So the total overall acceptance rate—the ratio of people who eventually receive an offer—would be closer to 30% than 7%.

At the same time, though, it’s also good to keep in mind that an application might be denied for any number of reasons, some of which are arbitrary or beyond the applicant’s control. For example, suppose you want to work with Professor X. But you don’t know that Professor X is taking a sabbatical, or has too many graduate students already, or has been diagnosed with a terminal illness and will not survive the length of your PhD, etc. You will be rejected. You will never know whether you were rejected for some of these invisible reasons or because you were simply not good enough. (I was rejected by nearly all of the institutions I applied to—I squeaked into my current program off of the waitlist at the last second.) In the face of this numbers game, the only viable strategy is to apply to a lot of schools. If you can’t afford the application fees, ask for a waiver.

The Vibe

If you imagine getting a PhD is something like an extended adolescence, wherein you and several other effortlessly cool, cigarette-smoking, young people lounge in cafés, having impassioned discussions about literature and philosophy, poor but scruffily happy, I have bad news for you. When you get a PhD, you are in essence an entry-level professional. You choose how to dress, it’s true, and to a large degree you control your own schedule. But chances are that you will dress in business casual, get up early in the morning, and work on a computer under fluorescent lights. It is the content rather than the form of the work that is distinctive. Literary scholars love to talk about transgressing boundaries, and they enjoy dissing things like the Protestant work ethic. In practice, however, literature professors are mostly conventional, cautious bureaucrats who value and reward temperance, dedication, consistency, and hard work. (I hasten to add that I do not think there is anything necessarily wrong with this: I value all of these things as well.)

So the vibe is “institutional.” But the vibe is also, at times, “institutional decline.” Universities aren’t doing so well these days, and the humanities are doing worse. Amid declining enrollment, shrinking budgets, and declining student interest in humanities degrees, it’s starting to feel just kind of over, the idea that you can get a PhD in literature. Outside of a few enclaves, these degree programs are not respected by the institutions that offer them or the public that funds them, trends that I do not see stopping any time soon. Universities haven’t yet phased literature PhD programs out, and the programs will probably limp along for a few decades before they are put out of their misery. But unless there are massive changes in the number of undergraduate students who attend college, the majors those students want to study, or the financial commitments of state legislatures and university administrators, the institutional humanities as we know them are a dead man walking, which lends the discipline a melancholy cast. I have no doubt that the study of literature will continue. However, I do doubt that universities will be at its center in twenty years.

But it’s not all as bleak as I am beginning to make it seem. One of my favorite essays of the past year was Joseph M. Keegin’s “Commit Lit,” in issue 33 of The Point. You should read it—it’s better than this post is—and it touches on why grad school might be worthwhile. “For forms of thinking that are essentially research disciplines,” writes Keegin, grad school is often “a bad trade-off. But philosophy is more than this: it is a way of life, a comportment of one’s concern and attention toward the pursuit of truth…we all have, we all seem to agree, one of the best jobs a person could imagine: we get to spend a few years in the company of great books, thoughtful colleagues and brilliant teachers.” I’m not a philosopher, but I think this applies to humanities disciplines more generally. I would add, too, that graduate school offers something that is truly precious and rare: the ability to think and write with genuine intellectual freedom, for a few years at least. People love to talk about how censorious the academy is, but I have never felt really unable to voice an opinion or perspective, at least as long as that opinion is substantive and thoughtful. My only limitations have been my own mind and my ability to work hard—significant limitations, but I have nobody to blame for that but myself. The real vibe is, then, neither “institutional” nor “institutional decline” but the juxtaposition of these bleak economic realities with the much more utopian ideals of free thought, self-development, and the pursuit of knowledge and beauty that are available, in real but constrained fashion, within the institution. It is this juxtaposition—sacred and profane, utopian and banal-dystopian, free and limited—that really defines what it feels like to get a literature PhD.

The Stipend

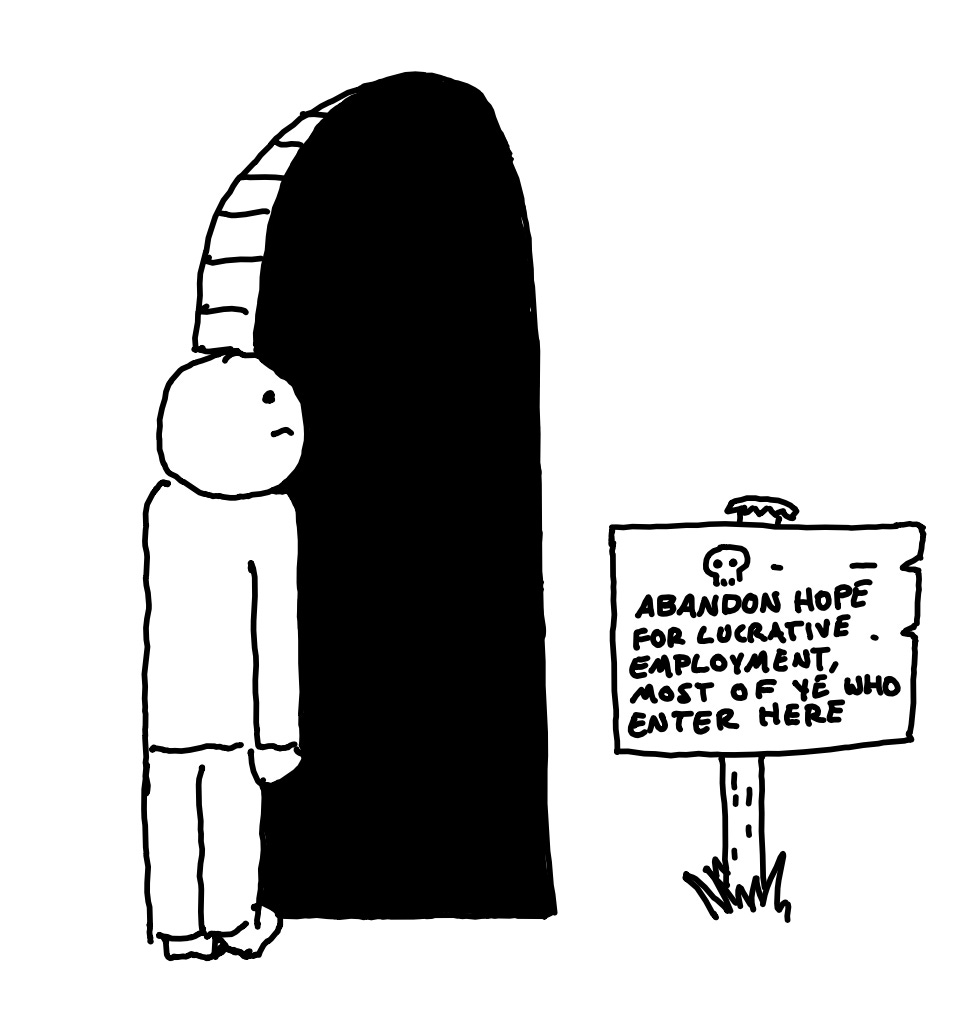

For most people, getting a PhD in literature is an unwise financial decision. There are far more newly minted PhDs than there are entry-level jobs in the field. You should not enter a PhD program under the assumption that you will become a professor at a university. You will not. So why enroll at all? For the sake of the work itself, for the chance to read, write, think, and teach for a few years. A humanities PhD is a trade-off. Some trade-offs are worth making; some aren’t. Such questions of value inevitably vary by person.

Every PhD student in a legitimate program pays no tuition and is paid an additional stipend to read, write, and teach, which is great. But they are not paid enough to sustain an independent life, which is less great! My stipend—a little over $23,000—is roughly commensurate with the stipends paid to students at similar universities in more expensive areas. Unfortunately, it is impossible qualify for a lease, even in a low-housing-cost city, if you make this little. (In the U.S. at least, low-income housing isn’t available if you’re a full-time student.) So you have three options: be supported by your family, be supported by a spouse or partner, or work a part-time job. Most PhD students have a partner who makes more money than they do who pays more than half the rent. I have received this kind of support and have worked part-time (teaching, freelancing, administrative work) for most of my degree. After five years of work, I’ve saved a few thousand dollars in a rainy-day fund and have a substantial amount of student debt (from previous degrees). If financial wealth is a priority, and you are not already rich, think twice about getting a PhD in literature, or in any other discipline that does not have clear industrial or military applications. I worry, sometimes, that I made a big financial mistake by enrolling, even though I knew the costs before going in, and I worry about debt and retirement and savings. Unless you are quite wealthy, such worries will become part of the warp and woof of your life if you do a literature PhD. The question was, for me, the price I was willing to pay to spend my workdays doing what I considered to be meaningful, pleasurable, and interesting work, at least for a while. For me, that price was high. If it’s not as high for you, that’s OK—after all, you can do a lot of reading on evenings and weekends, and there are growing opportunities for intellectual community outside of academia.

The Structure of a PhD Program

It usually takes between five and six years to get a PhD in literature if you don’t dilly-dally or experience any personal tragedies or need to work full time. (Average time to degree, in real life, is around seven years.) The degree has three phases: coursework, lists, and candidacy. Coursework, which usually lasts the first two years, is the most difficult of the three—you must take classes, which usually meet once a week for three hours straight to discuss assigned readings. PhD students are expected to read a total of 2-4 books per week and to write two or three 25-page “seminar papers” (baby peer-reviewed journal articles, which are in my opinion a waste of time unless you end up revising and publishing them). You will find yourself working—that is, reading, writing, teaching, grading, attending class, working your second job, and so on—for between 60 and 70 hours per week. This is, for most people, physically unhealthy, noxious to social and family life, and often unpleasant. (Ask any first- or second-year PhD student, “How are you doing?” and note the deep sigh that will normally precede their response.) On the other hand, you get to sit around reading, thinking, and teaching all day, and as far as I’m concerned, there just isn’t a better job.

The second phase of a PhD, lists, varies widely by institution. The basic gist is that must read 75-100 books in the space of two semesters, taking copious notes. At the end of the process, you take an exam that evaluates your knowledge of what you’ve read. Oral exams—the kind I took—take the form of a 90-minute conversation in which you are asked quite specific questions about the books you read. Written exams—as far as I can tell—take the form of a 60-or-so-page essay in which you summarize, broadly, what you read. The list year was also very stressful; in the few weeks before my exams, I found myself struggling to sleep and having little moments of panic. But the truth is that, if you make it past your coursework, the possibility that you will flunk out is distant indeed. And your lists will offer you the opportunity to become not just familiar but intimate with your subject matter. Dedicated and focused reading over the span of a year is probably the fastest way to develop this intimacy, which is one of the best sensations my program has offered me.

The third phase of a PhD, candidacy, is by far the best part—if you have a good committee. Here, your primary job is to write (usually while you teach). You select three or more professors to serve on your “committee.” These are the people who will help you develop your dissertation, give you feedback on successive drafts, and give you advice on how to approach your career. If you have a good committee—and I am fortunate to have one—this is a time when you are really living the dream. I spend most of my days reading and writing! That’s my main job! (And my part-time job doesn’t take too much time!) Most people never get this insane luxury. It won’t last—my fellowship gives out soon—but until then, I am living my childhood dream. It’s another six months or a year until I’m punching the clock like everyone else, but for now, I get to write and learn and think all day. I’m not teaching this year, so my normal weekday looks like: wake up, exercise, breakfast, check emails and messages, then read or write for a few hours. After lunch, I’ll read and write some more, then take care of some administrative or other work tasks. This is truly a form of paradise, and it’s one that I am grateful I get to live out every day, even if the stipends are low.

The Teaching

Most PhD students are expected to teach in return for their stipend. Except for the past few months, I have taught at least one class per semester since August of 2020. Teaching is both exhilarating and exhausting. Generally speaking, PhD students teach the courses that account for much of the enrollment of English departments but which tenured literature faculty do not want to teach: introductory writing courses—ENG 101 and 102 at many institutions.

When it works—when you watch someone grow and develop and contribute in some small way to that process—it’s great. Young people can be inspiring and charming, and they can say startlingly insightful, hilarious, and interesting things in class discussions. Some of my favorite teaching memories have been with students who simply come to my office hours to hang out and talk about books, life, whatever. One student exhaustively showed me the computer game project she was working on and explained how she could make money from it. Another student once asked me whether she should commit an act of revenge against someone who had wronged her (when I advised her not to, she asked, “But what if that makes me seem like a little bitch?”). Some students have written me thank-you cards or given me little gifts at the end of the semester expressing gratitude for my class, which is just lovely. Working with students like these remind me how full of life and possibility young people are. It’s beautiful and meaningful work.

It’s not all beautiful, of course. Many students are mentally and spiritually checked out, at least while they are in class. There is little that can be done for such students unless they decide to participate. Of the many clichés that have been validated by my experience as a teacher, “You can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make it drink” is perhaps the most apt. Many students have been taught, directly and indirectly, to see education solely as a means to an end, an intrinsically meaningless activity that must be completed to satisfy an arbitrary and inscrutable employment system. (Descriptively, by the way, this is not an inaccurate understanding of the American education system, although of course I don’t think that’s what education should be.) It is difficult to jolt them out of this, especially within the constraints of a first-year writing course.

If I have any practical advice for a PhD student worried about teaching, it would be:

The more time and effort you put into preparing for a class, the better the class will generally work. However, the more time and effort you put into preparing for class, the less time you will have for your own coursework and research.

Complicated teaching technology is a managerial nightmare and does not tend to noticeably improve student outcomes. You find yourself spending most of your time teaching students how to use their “revolutionary” new piece of software instead of the subject matter you are putatively supposed to teach.

Rigidly structured courses (no late submissions, grades returned according to a specific schedule, no changes to the readings, and so on) earn students’ trust, are on average more fair, and require far less time from you. The more flexible and improvisatory your course is, the more time you will spend doing rote administrative work and the more confused your students will become. It is OK to be strict. In most cases, there is nothing ethically wrong about failing a student because she did not turn her work in on time (or at all). You don’t have to feel guilty about that, even if the student would like you to.

You will not reach or transform every student. This does not mean that there is something wrong with you. But, eventually, you will reach some, and it’s a very meaningful accomplishment.

What I Learned

You’re supposed to learn at school, so what have I learned while doing my PhD?

How to write. I think I’ve grown a lot as a writer, largely because of feedback that I’ve gotten from professors, committee members, and peer reviewers. This isn’t to say that I am currently a great writer—just that I’m better than I was five years ago, mostly because I have had to generate hundreds of pages of writing, then revise those pages. However, much of this writing was not required by my program. Submitting to peer-reviewed journals, giving public lectures, and writing blog posts like this one have helped me grow just as much as seminar papers and dissertation work have. I love writing—there is no other task quite so absorbing, for me—and the amount of time I have been allowed to spend writing has been the chief blessing of my PhD experience.

Subject matter expertise. My research focuses on nineteenth-century American literature and culture. I certainly don’t know everything about this area, but I know much more than I used to, simply because I have, once again, read thousands and thousands of pages. The PhD gave me the time, structure, and motivation to do that reading, as well as experts and fellow students to talk to. Conversation is an extremely effective way to develop expertise.

General professional skills. In my PhD, I’ve had to do all kinds of stuff, including helping to manage an organization, conducting policy reviews, serving on committees, all that jazz. This has helped me begin to learn how to be a functional cog in the complex machinery of a vast institution. Again, most of this was not a required element of my program.

Teaching and public speaking. If you speak in front of a group of 30 people two or three times a week for five years, you simply will get better at public speaking. I’ve also learned a lot about how to construct lessons and lectures, lead discussions, and so on.

What I Didn’t Learn

Broad knowledge. I thought that, by the end of a PhD program, I would be “well-read”—which is to say that I’d have a solid grasp of world history, would have read plenty of the Great Books, and would have pretty well-defined philosophical and political positions. But PhDs, especially the last few years, focus more on developing deep expertise on a pretty narrow field. Even in a PhD program, being well-read in the way that I imagined has been at least partially a personal project, a hobby, rather than an integral part of my institutional education.

How to make money. Nobody really knows how to employ a literature PhD outside of the crumbling edifice that is humanities academia; PhDs are simply not vocational in the same way that, say, a master’s degree in nursing is. While I’ve picked up some marketable skills, I do not really know how I will transform those marketable skills into rent payments upon my graduation.

The End

I haven’t finished my program yet, although I am trying to be done by this May. I do not know what it feels like to finish a PhD. My sense is that it will feel rather anticlimactic.

—

More posts about academia:

“Professional Criticism”—on writing a peer-reviewed article in a fancy journal

“The Job Market in Literary Studies is Never Getting Better”

“Against False Rigor”—on teaching academic writing

This is both hilarious and depressing: "In practice, however, literature professors are mostly conventional, cautious bureaucrats who value and reward temperance, dedication, consistency, and hard work."

I recognize so much in this essay, particularly the sense that I was breaking the usual rules of the working world, enjoying "some kind of paradise." I now see it much differently. I finished my PhD in 3.5 years at the age of 29, weathered a crushing first year "on the market," and landed a visiting position that turned into a tenure-track role. Once on the tenure track, I advanced quickly to full rank (~8 years). So in that sense I made it.

But what looked like paradise to me in my 20s, when I enjoyed things like backpacking around Europe or the Idaho wilderness, looked differently to me in my 40s, when I was raising a family. By the time someone completes a PhD, they've already sacrificed a considerable amount of earnings and retirement savings. You never really get that back. When I resigned my position at age 46, my annual salary was about the same as the starting salary for a personal banker. By that time I also had three kids (not part of my plan in grad school). When you start thinking about how you'll pay for your kids' college education, the whole thing looks even less satisfying.

You're not asking for advice, but I'll give it anyway. If I were in your position, preparing to graduate in May, almost assuredly applying to every job in sight with very little likelihood of landing more than a lectureship the first year, I would also spend some time thinking about non-academic roles, networking on LinkedIn, maybe even working with a career coach specializing in transitioning PhDs. Carve out time to plan your exit, because you'll need it.

Happy to share any of the interviews I've done with former academics, if that would help. If you can't hear the urgency in this statement, I sure do: "While I’ve picked up some marketable skills, I do not really know how I will transform those marketable skills into rent payments upon my graduation."

This was sooooo fun to read. You have a great writing style. I’m hearing back from PhDs in the spring and have mostly heard this stuff but you made it so concise and logical and informative. Good luck and I’m excited to read your dissertation if you post it here.