I teach introductory academic writing to first-year university students. When I grade student papers, I tend not to grade them based on whether they are interesting or, in the final analysis, worth reading. Instead, I grade them on more directly measurable and quantifiable metrics: Did they reach the word count? Was their paper formatted correctly? Is it on topic? Did they follow directions? Does the paper attempt to accomplish the intellectual work I asked for? Is the student demonstrating the sorts of skills they’ll need to succeed in college and beyond?

Most of my students have never before been introduced to the proposition that writing a paper can be anything other than a metric-tested, standards-bound, rote activity done to satisfy the arbitrary whims of an inscrutable education system that does not have their best interests at heart. To ask these students to radically revise their notion of academic writing in a single semester—to expect them to realize that they can bring to essay writing the same degree of imaginative enthusiasm that they bring to the things in their life they actually care about— would be unreasonable at best and cruel at worst. The idea that we write to think carefully about real life, about things that really matter, is so alien to most of my students that it is almost unthinkable. I try to nudge them in that direction. I coax and encourage. But I do not expect it, and I don’t hold them to that standard.

Beyond this, though, I want students to feel like their grade is based on something demonstrable and measurable. If the essay is simply shorter—or if it isn’t formatted according to the MLA stylebook—they understand why they receive a lower grade. There’s nothing subjective about a missing hanging indent. If I were to give a student a C because they wrote a boring, unimaginative, insipid, predictable paper that ultimately said nothing of importance, interest, or benefit, they would protest, asking how I can claim to be the arbiter of such things. So, when I grade my students, I don’t grade them on whether I think their writing is good. I grade them on the things that I can count.

In literary studies, I often think that peer reviewers do something similar. If the content of academic journals is any indication, peer-reviewed papers are not necessarily judged on whether they are exciting or interesting, or on whether they contain any useful information, or whether their interpretive claims matter outside of the strange realm that is academic literary criticism, or even on whether their arguments are convincing. After making it to peer review—and it seems to me that most essays that are about a relevant topic, that reach the word count, and so on get to peer review—the primary standards for most peer reviewers seem to be:

Does the paper cite every major related source, especially publications from the last twenty years in a way that demonstrates that the author read those sources with some care and comprehension?

Even if the essay doesn’t convince the reader, do the arguments seem to make sense?

Does the paper clearly show that it’s saying something new?

Generally speaking, is the prose understandable?

I tend to give my students an A if they did everything right and put the right amount of work in. Similarly, pretty much any essay that meets the above standards (that is, that obeys certain genre rules) will probably be published—perhaps not in the most prestigious journals, but almost certainly in less competitive journals. The problem with these standards is that they don’t always have much to do with whether the essay is any good. They are generic rather than substantive. This sort of work can be churned out.

And, I think, we all know that some academic work is churned out. Why else would literary characters like Casaubon, the middling intellectual doomed to irrelevance in Middlemarch, or Jim Dixon from Lucky Jim, with his superfluous and tedious article on shipbuilding, so fascinate and disturb us? Peer-reviewed publications are building blocks for careers, and for a long time I have wanted an academic career. So, out of a sense of obligation, I am incentivized to write, publish, and read “rigorous” work (footnoted, with tortuous sentences and precisely-formatted bibliographic citations) that, as far as human needs and concerns go, may as well not exist. Of course, if you are a humanist reading this, there is no doubt that your scholarship is important and readable and interesting—but I’m sure that you can think of colleagues whose work fits this description. To keep the academic ship afloat, it seems to me that we nod along, approving the publication of scholarship that is correct, according to a science-like rubric, but which addresses no real need, expresses no recognizable attitude, but sits dutifully on the page, waiting for the next graduate student to pore through it because they need to cite it in the hopes that their essay on medieval shipbuilding, too, will pass muster.

We all know perfectly well that insipid tedium gets published in academic journals from time to time (often using a language of political radicalism, or audaciously counterintuitive claims, to add piquancy to an essentially bland dish). Sure, it got published, we will readily admit, but it wasn’t really good. Like our students, we are writing to satisfy the arbitrary whims of an inscrutable education system that, I am sorry to say, does not have our best interests at heart.

So why does the academic system use the standards it uses? Partially, reviewers want to make sure that our thinking is of the highest caliber—and many well-intentioned peer reviewers see the generic norms of academic writing as a way to defend serious standards. But I think a large reason our disciplines value this process is to convince others that literary scholarship is legitimate, that the knowledge we produce matters—or, at the very least, that is it recognizably knowledge (in other words, that it looks official and vaguely science-like). But this effort to represent ourselves as rigorous is failing: confidence in higher education is dropping as the humanities continue to be defunded amidst critiques from both Democrats and Republicans.

Last year, English professor Aaron Hanlon argued that the humanities are facing a legitimacy crisis. This legitimacy crisis is born of the fact that humanities knowledge isn’t useful in a utilitarian or industrial sense. In a humanities classroom, you can’t learn how to treat cancer, build a surface-to-air missile, or any of the other technological or industrial tasks that our society seems to value. Insofar as universities are institutions that credential productive workers, this limitation is a failure, perhaps a fatal one. And as some legislators and university administrators strive to make the credentialing of productive workers the sole aim of the university, there is no room left for humanistic study.

There are two ways out of this crisis, for Hanlon. First, we can understand the humanities as practical, useful “knowledge work,” which means tailoring the humanities to serve, rather than oppose, the needs of institutions like universities, governments, and business in order to secure funding and support from those institutions. In realistic, practical terms, this seems to me like it would entail the complete transformation of English departments from centers of literary study to centers of rhetoric and composition, although perhaps there are ways of integrating literary scholarship into obviously economically productive research that I am incapable of imagining. (This might look like using AI models to predict what kinds of blockbuster movies audiences find most compelling, but the defunding of more obviously economically useful research departments, like mathematics, makes me skeptical that institutions would really invest in this kind of work, and if they did, it would be rather depressing.) I am not primarily in favor of this model. It would not save those things about literary scholarship that are worth saving. And, on a personal note, I would rather work outside of the university than teach five sections of technical writing per semester, although I do not disparage those who are willing to do so.

The other way out of this crisis, as Hanlon puts it, is to maintain the humanities’ opposition to economic utility, thereby giving up on institutional support and its associated benefits (tenure, funding, stability) but regaining some public trust—or, at least, trust among some publics. This would relegate humanities work either to hobbyists (to whom I doff my hat with respect) or to those humanists who can find a paying audience for their writing (or podcasts, or videos, or, you know, Substacks, or whatever).

The necessity that we find an audience for our writing is a far different, and in some ways more demanding, task than the necessity that we successfully navigate the peer review system. We will need to write far more and make that writing funny, engaging, and satisfying to readers who are under no professional obligation to slog through our stuff. (I’m trying here, but good grief, it’s not easy.) We’ll need to write for an audience that is less well-informed and more politically heterogeneous than literary scholars tend to be. Instead of responding to “the literature,” we’ll have to respond to an audience by using our writing to bring them something that they want: a new perspective, an answer to an urgent or perennial human question, or, at the very least, a good time.

The way our scholarship currently maintains its ever more tenuous claim to legitimacy is by dressing up in a suit that looks like a scientific article. Rather than lending ourselves credibility, this act makes it appear as though we are attempting to make our claims more empirical and literal than they in fact are. And it makes our writing less appealing to the very publics on whom we may soon depend.

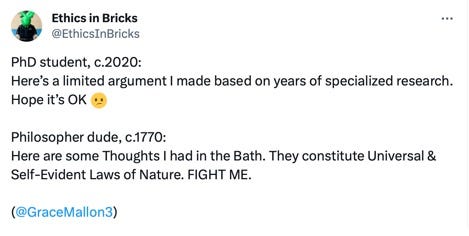

At our best, I think that literary and cultural critics are fooling around, using our imaginations, gambling on provisional and risky claims, using figurative language, thinking associatively, writing about their vibes and hunches and airy speculations. Our work is often partisan, autobiographical, idiosyncratic. It is imaginative, not lemmatical. This seems good to me, and I think we should keep doing it, because I think a ludic, non-literal approach to thought is a necessary counterpart to the grim technocracy of our age, and because this kind of thinking reveals insights that are inaccessible to empirical investigation. Such thinking can be done well or poorly, but we must measure it by its own rubric, one which I think should be far more ruled by the caprices of taste, temperament, and subjectivity than we would like to admit. Not only do academic standards of rigor not necessarily make our work more rigorous, they also makes it less readable and more open to the sorts of bad-faith critiques that have (in tandem with austerity thinking, the valorization of what the ancient Greeks called the servile arts at the expense of the liberal arts, and drooping interest in literary matters among young people) so damaged the organized, funded humanities. It causes us to turn our attention not toward questions that matter or are of intrinsic interest to readers, but toward questions that have been prompted by preceding generations of literary scholars. As organized literary study shrinks in the face of austerity, and as we turn to public audiences as a source of support, this kind of writing simply won’t do. We need, I think, a new rubric for thinking about how young and developing humanists should direct their inquiry and develop as writers.

Agree with your last paragraph. As Ray Bradbury once said of fiction and of painting, it's play at its highest level.

To play devil's advocate, at the same time I think even criticism/literary history/etc. needs a certain baseline of factual accuracy. For example, a film critic should at least avoid major factual errors about the film in question and its production.