Most writers don’t make a living from selling books (or newsletter subscriptions, or whatever). To make money, they usually teach others how to write. This is generally true across creative domains: it is much easier to make a living as a teacher of writing than as a writer; it is easier to become a drama teacher than a successful actor; and, generally speaking, the most reliable way to make a living in music is to teach lessons, not to start a band.

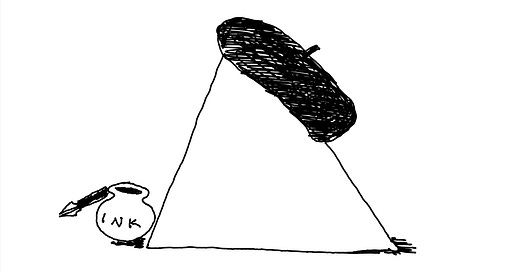

There is, in other words, a pyramid-scheme-like structure to most creative fields. In a pyramid scheme, money isn’t generated from the sale of goods or services but from the enrollment of others in the scheme. Those at the bottom of a pyramid scheme invest in a company by purchasing products, which are usually useless, and which they now must sell in order to recoup their losses. Since the products are usually not in real high demand, the best way to sell those products is not to sell them to consumers as products but to sell them to other prospective entrepreneurs as a business opportunity. If you can dangle a vision of a wonderful life full of ease and Caribbean vacations in front of a desperate, frustrated or unemployed person, and if they are a little gullible, this is not very difficult.

If you have an MFA or a PhD in the humanities, or have in some other way dedicated yourself to a craft that doesn’t pay, you have the equivalent of a pallet full of unwanted essential oils or energy drinks sitting in your garage. You’ve invested your time and hard work in this thing that nobody wants to buy, so you’d better find some poor sap to offload it onto, so they can sell it to someone else, and so on and so on. So, if the writing thing doesn’t quite work out, you might position yourself as a coach, guru, teacher, professor of practice, and so on. As it turns out, there are plenty of paying customers who want to be writerly. A frustrated person with dreams of being a successful entrepreneur is an easier mark than a customer who actually has to drink the energy drink. Similarly, a frustrated person with dreams of being a writer is an easier mark than a reading audience.

I should pause here and say that I don’t think that anyone should be ashamed of this kind of work. I will probably in fact do plenty of it in my life, because I will take a life full of writing however I can find it. But this dynamic presents problems that can make our writing less interesting.

The biggest problem I can see is that it leads us to write, unendingly, about writing. You may have noticed the subgenre of Substack posts with headlines like “How I Reached X Subscribers on Substack.” Often, these appear to be the most popular articles on a particular Substack. This is not because the writing itself is necessarily better, or that growing a newsletter is an intrinsically fascinating topic that general readers are obsessed with. It is because the audience of many Substack writers is other, less successful Substack writers, who are often reading and “engaging” with one another’s work not because the work is itself of interest but because it might help them attract readers to their own Substacks.

Plenty of the engagement on Notes or in the comments section of this site also stems from a desire to have one’s own work read. (This probably explains the unrelenting positivity, verging on smarm, that defines the Notes platform, at least in my experience.) If I post a comment that showed that I read your article, you might be more likely to post a comment on my article that showed that you read it. It’s a slightly more subtle and well-mannered “sub4sub” arrangement. We call it “building community.”

This isn’t necessarily wrong or unethical. I may have done a little bit of this myself. (I think I’m genuinely interested in the blogs I read and comment on on here, but who knows? Am I transparent to myself?) And this dynamic plays out in other venues, too. The vast majority of people who read prestigious literary magazines, for example, do so in order to figure out how to get their own stories published in a prestigious literary magazine.

The pyramid structure encourages a certain beady-eyed and cynical mode of reading: it leads me to read as a means to a practical end—not to satisfy my curiosity or to entertain myself, but to get something out of the reading, something I can cash out, something I can use to wrestle my way up the hierarchy of aspiring writers. In this mode of reading, personal lyric essays are treated as little more than microwave manuals: useful guides to practical action, something to be used. Reading a lyric essay like this is like using a piano as a doorstop. It’s certainly practical, and there’s nothing straightforwardly unethical about it, but there’s no music happening, and that is, after all, what a piano is for.

Worse, when we realize that writing about writing works better than writing about anything else, we might start trying to write primarily or only about writing. This would entail a narrowing of our intellectual lives. If this happened long enough, entire networks of writers would write about nothing but writing. Their creative products would be unread and unpopular compared to their real blockbusters, which would be guides to writing writing about writing. (Or, creepier, Machiavellian guides to engineering an audience.) Even novels would be read not as pieces of art but examples of a genre, which could be reverse-engineered to discover what makes the novel tick. Of course, if one wants to be a writer, some degree of this reverse-engineering is necessary. We do need to think and talk about craft. But just as vitally, we need to talk and think about, you know, real life. There’s a reason that the MFA novel—the polished, stately, but ultimately empty cultural artifact—is the subject of occasional withering critique. Craft is a boat, but that boat needs to be steered in some worthwhile direction. We all want audiences, but I assume that we want audiences because we care about the same things or because they legitimately enjoy the experience of reading our writing, not because our writing provides to our audience a kind of mercenary value. If writing slowly becomes about nothing but writing (or, like this essay, writing about writing writing), it will slowly detach from the real world, becoming less and less accessible or valuable to anyone but a shrinking coterie of hobbyists.

God forbid!